If you subscribe to an event in C# and forget to unsubscribe, does it cause a memory leak? Always? Never? Or only in special circumstances? Maybe we should make it our practice to always unsubscribe just in case there is a problem. But then again, the Visual Studio designer generated code doesn’t bother to unsubscribe, so surely that means it doesn’t matter?.

updater.Finished += new EventHandler(OnUpdaterFinished);

updater.Begin();

...

// is this important? do we have to unsubscribe?

updater.Finished -= new EventHandler(OnUpdaterFinished);

Fortunately it is quite easy to see for ourselves whether any memory is leaked when we forget to unsubscribe. Let’s create a simple Windows Forms application that creates lots of objects, and subscribe to an event on each of the objects, without bothering to unsubscribe. To make life easier for ourselves, we’ll keep count of how many get created, and how many get deleted by the garbage collector, by reducing a count in their finalizer, which the garbage collector will call.

Here’s the object we’ll be creating lots of instances of:

public class ShortLivedEventRaiser

{

public static int Count;

public event EventHandler OnSomething;

public ShortLivedEventRaiser()

{

Interlocked.Increment(ref Count);

}

protected void RaiseOnSomething(EventArgs e)

{

EventHandler handler = OnSomething;

if (handler != null) handler(this, e);

}

~ShortLivedEventRaiser()

{

Interlocked.Decrement(ref Count);

}

}

and here’s the code we’ll use to test it:

private void OnSubscribeToShortlivedObjectsClick(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

int count = 10000;

for (int n = 0; n < count; n++)

{

var shortlived = new ShortLivedEventRaiser();

shortlived.OnSomething += ShortlivedOnOnSomething;

}

shortlivedEventRaiserCreated += count;

}

private void ShortlivedOnOnSomething(object sender, EventArgs eventArgs)

{

// just to prove that there is no smoke and mirrors, our event handler will do something involving the form

Text = "Got an event from a short-lived event raiser";

}

I’ve added a background timer on the form, which reports every second how many instances are still in memory. I also added a garbage collect button, to force the garbage collector to do a full collect on demand.

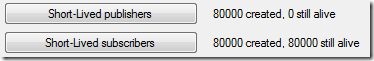

So we click our button a few times to create 80,000 objects, and quite soon after we see the garbage collector run and reduce the object count. It doesn’t delete all of them, but this is not because we have a memory leak. It is simply that the garbage collector doesn’t always do a full collection. If we press our garbage collect button, we’ll see that the number of objects we created drops down to 0. So no memory leaks! We didn’t unsubscribe and there was nothing to worry about.

But let’s try something different. Instead of subscribing to an event on my 80,000 objects, I’ll let them subscribe to an event on my Form. Now when we click our button eight times to create 80,000 of these objects, we see that the number in memory stays at 80,000. We can click the Garbage Collect button as many times as we want, and the number won’t go down. We’ve got a memory leak!

Here’s the second class:

public class ShortLivedEventSubscriber

{

public static int Count;

public string LatestText { get; private set; }

public ShortLivedEventSubscriber(Control c)

{

Interlocked.Increment(ref Count);

c.TextChanged += OnTextChanged;

}

private void OnTextChanged(object sender, EventArgs eventArgs)

{

LatestText = ((Control) sender).Text;

}

~ShortLivedEventSubscriber()

{

Interlocked.Decrement(ref Count);

}

}

and the code that creates instances of it:

private void OnShortlivedEventSubscribersClick(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

int count = 10000;

for (int n = 0; n < count; n++)

{

var shortlived2 = new ShortLivedEventSubscriber(this);

}

shortlivedEventSubscriberCreated += count;

}

and here’s the result:

So why does this leak, when the first doesn’t? The answer is that event publishers keep their subscribers alive. If the publisher is short-lived compared to the subscriber, this doesn’t matter. But if the publisher lives on for the life-time of the application, then every subscriber will also be kept alive. In our first example, the 80,000 objects were the publishers, and they were keeping the main form alive. But it didn’t matter because our main form was supposed to be still alive. But in the second example, the main form was the publisher, and it kept all 80,000 of its subscribers alive, long after we stopped caring about them.

The reason for this is that under the hood, the .NET events model is simply an implementation of the observer pattern. In the observer pattern, anyone who wants to “observe” an event registers with the class that raises the event. It keeps hold of a list of observers, allowing it to call each one in turn when the event occurs. So the observed class holds references to all its observers.

What does this mean?

The good news is that in a lot of cases, you are subscribing to an event raised by an object whose lifetime is equal or shorter than that of the subscribing class. That’s why a Windows Forms or WPF control can subscribe to events raised by child controls without the need to unsubscribe, since those child controls will not live beyond the lifetime of their container.

When it goes wrong is when you have a class that will exist for the lifetime of your application, raising events whose subscribers were supposed to be transitory. Imagine your application has a order service which allows you to submit new orders and also has an event that is raised whenever an order’s status changes.

orderService.SubmitOrder(order);

// get notified if an order status is changed

orderService.OrderStatusChanged += OnOrderStatusChanged;

Now this could well cause a memory leak, as whatever class contains the OnOrderStatusChanged event handler will be kept alive for the duration of the application run. And it will also keep alive any objects it holds references to, resulting in a potentially large memory leak. This means that if you subscribe to an event raised by a long-lived service, you must remember to unsubscribe.

What about Event Aggregators?

Event aggregators offer an alternative to traditional C# events, with the additional benefit of completely decoupling the publisher and subscribers of events. Anyone who can access the event aggregator can publish an event onto it, and it can be subscribed to from anyone else with access to the event aggregator.

But are event aggregators subject to memory leaks? Do they leak in the same way that regular event handlers do, or do the rules change? We can test this out for ourselves, using the same approach as before.

For this example, I’ll be using an extremely elegant event aggregator built by José Romaniello using Reactive Extensions. The whole thing is implemented in about a dozen of code thanks to the power of the Rx framework.

First, we’ll simulate many short-lived publishers with a single long-lived subscriber (our main form). Here’s our short-lived publisher object:

public class ShortLivedEventPublisher

{

public static int Count;

private readonly IEventPublisher publisher;

public ShortLivedEventPublisher(IEventPublisher publisher)

{

this.publisher = publisher;

Interlocked.Increment(ref Count);

}

public void PublishSomething()

{

publisher.Publish("Hello world");

}

~ShortLivedEventPublisher()

{

Interlocked.Decrement(ref Count);

}

}

And we’ll also try many short-lived subscribers with a single long-lived publisher (our main form):

public class ShortLivedEventBusSubscriber

{

public static int Count;

public string LatestMessage { get; private set; }

public ShortLivedEventBusSubscriber(IEventPublisher publisher)

{

Interlocked.Increment(ref Count);

publisher.GetEvent<string>().Subscribe(s => LatestMessage = s);

}

~ShortLivedEventBusSubscriber()

{

Interlocked.Decrement(ref Count);

}

}

What happens when we create thousands of each of these objects?

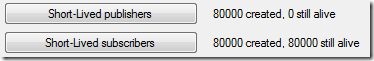

We have exactly the same memory leak again – publishers can be garbage collected, but subscribers are kept alive. Using an event aggregator hasn’t made the problem any better or worse. Event aggregators should be chosen for the architectural benefits they offer rather than as a way to fix your memory management problems (although as we shall see shortly, they encapsulate one possible fix).

How can I avoid memory leaks?

So how can we write event-driven code in a way that will never leak memory? There are two main approaches you can take.

1. Always remember to unsubscribe if you are a short-lived object subscribing to an event from a long-lived object. The C# language support for events is less than ideal. The C# language offers the += and -= operators for subscribing and unsubscribing, but this can be quite confusing.Here’s how you would unsubscribe from a button click handler…

button.Clicked += new EventHandler(OnButtonClicked)

...

button.Clicked –= new EventHandler(OnButtonClicked)

It’s confusing because the object we unsubscribe with is clearly a different object to the one we subscribed with, but under the hood .NET works out the right thing to do. But if you are using the lambda syntax, it is a lot less clear what goes on the right hand side of the –= (see this stack overflow question for more info). You don’t exactly want to keep trying to replicate the same lambda statement in two places.

button.Clicked += (sender, args) => MessageBox.Show(“Button was clicked”);

// how to unsubscribe?

This is where event aggregators can offer a slightly nicer experience. They will typically have an “unregister” or an “unsubscribe” method. The Rx version I used above returns an IDisposable object when you call subscribe. I like this approach as it means you can either use it in a using block, or store the returned value as a class member, and make your class Disposable too, implementing the standard .NET practice for resource cleanup and flagging up to users of your class that it needs to be disposed.

2. Use weak references. But what if you don’t trust yourself, or your fellow developers to always remember to unsubscribe? Is there another solution? The answer is yes, you can use weak references. A weak reference holds a reference to a .NET object, but allows the garbage collector to delete it if there are no other regular references to it.

The trouble is, how do you attach a weak event handler to a regular .NET event? The answer is, with great difficulty, although some clever people have come up with ingenious ways of doing this. Event aggregators have an advantage here in that they can offer weak references as a feature if wanted, hiding the complexity of working with weak references from the end user. For example, the “Messenger” class that comes with MVVM Light uses weak references.

So for my final test, I’ll make an event aggregator that uses weak references. I could try to update the Rx version, but to keep things simple, I’ll just make my own basic (and not threadsafe) event aggregator using weak references. Here’s the code:

public class WeakEventAggregator

{

class WeakAction

{

private WeakReference weakReference;

public WeakAction(object action)

{

weakReference = new WeakReference(action);

}

public bool IsAlive

{

get { return weakReference.IsAlive; }

}

public void Execute<TEvent>(TEvent param)

{

var action = (Action<TEvent>) weakReference.Target;

action.Invoke(param);

}

}

private readonly ConcurrentDictionary<Type, List<WeakAction>> subscriptions

= new ConcurrentDictionary<Type, List<WeakAction>>();

public void Subscribe<TEvent>(Action<TEvent> action)

{

var subscribers = subscriptions.GetOrAdd(typeof (TEvent), t => new List<WeakAction>());

subscribers.Add(new WeakAction(action));

}

public void Publish<TEvent>(TEvent sampleEvent)

{

List<WeakAction> subscribers;

if (subscriptions.TryGetValue(typeof(TEvent), out subscribers))

{

subscribers.RemoveAll(x => !x.IsAlive);

subscribers.ForEach(x => x.Execute<TEvent>(sampleEvent));

}

}

}

Now let’s see if it works by creating some short-lived subscribers that subscribe to events on the WeakEventAggregator. Here are the objects, we’ll be using in this last example:

public class ShortLivedWeakEventSubscriber

{

public static int Count;

public string LatestMessage { get; private set; }

public ShortLivedWeakEventSubscriber(WeakEventAggregator weakEventAggregator)

{

Interlocked.Increment(ref Count);

weakEventAggregator.Subscribe<string>(OnMessageReceived);

}

private void OnMessageReceived(string s)

{

LatestMessage = s;

}

~ShortLivedWeakEventSubscriber()

{

Interlocked.Decrement(ref Count);

}

}

And we create another 80,000, do a garbage collect, and finally we can have event subscribers that don’t leak memory:

My example application is available for download on BitBucket if you want

Conclusion

Although many (possibly most) use cases of events do not leak memory, it is important for all .NET developers to understand the circumstances in which they might leak memory. I’m not sure there is a single “best practice” for avoiding memory leaks. In many cases, simply remembering to unsubscribe when you are finished wanting to receive messages is the right thing to do. But if you are using an event aggregator you’ll be able to take advantage of the benefits of weak references quite easily.